The Lost Searcher: Edward Carre and the Warburton Mystery

Read the Mary Warburton Story here: Part I | Part II | Part III

What happened to nurse Mary Warburton? It’s a question Edward Carre took it upon himself to answer after she disappeared on the Indian River Trail in 1931. His obsession with solving the case led him down the same trail and nearly the same fate.

Edward Carre was born in Belgium in 1871. By the early 1900s, he had married and settled in Vancouver. Over the years, he worked as an engineer for St. Paul’s Hospital, the Provincial School for the Deaf and Blind, and the Vancouver School Board. By the early 1930s, he was working as a janitor at a Vancouver school, and he loved the outdoors.

The Warburton case fascinated Carre enough to go out looking for her body on the Indian River Trail in 1934. Accompanied by Constable Gill, who had been in charge of the original search for Warburton, he reached the cabin where she had left a note after taking shelter.

In a newspaper article about the trip, the theory Carre put forward was that Warburton fell into Windy Creek and drowned, and that her body was never found because her heavy pack held it underwater. The theory was apparently corroborated by the trapper who found Warburton’s last footprints, who said he saw them on a log over the creek but not on the other side. This is in contrast to previous reports, which stated that her footprints couldn’t be followed further due to fresh snowfall.

Regardless of Mary Warburton’s ultimate fate, Carre’s fascination with the case led to a determination to complete the trail himself.

Carre’s Waterloo

For several years in a row, Carre attempted to hike the entirety of the Indian River Trail, much to his wife’s exasperation. She called it his Waterloo, and on his 1936 attempt, he was about to be defeated again.

Though he’d spent a great deal of time at the western end of the trail, presumably in the area that Warburton had disappeared, Carre was not an experienced hiker. He was said to be a lover of the outdoors and athletic for a 64-year-old, but not experienced in terrain described as steep, rugged, inhospitable, and mountainous. In fact, his friends and family warned him off the trip, but he wasn’t deterred.

He left Vancouver for Squamish on August 6, 1936. At the time, there was only a rough service road connection between the communities, and no rail line, so Carre travelled by steamship. Though he’d hoped to find a companion before he set off, ultimately he went alone, beginning his trek on August 7. He intended for the trip to take a week and had brought enough food for that time, as well as a rifle, fishing tackle, and other camping supplies.

He was expected back at work on Thursday, the 20th, but when he didn’t turn up, his wife called the police, and once again a search was mounted for a lone sixty-something hiker lost on the Indian River Trail.

Rough, Rugged, and Notoriously Overgrown

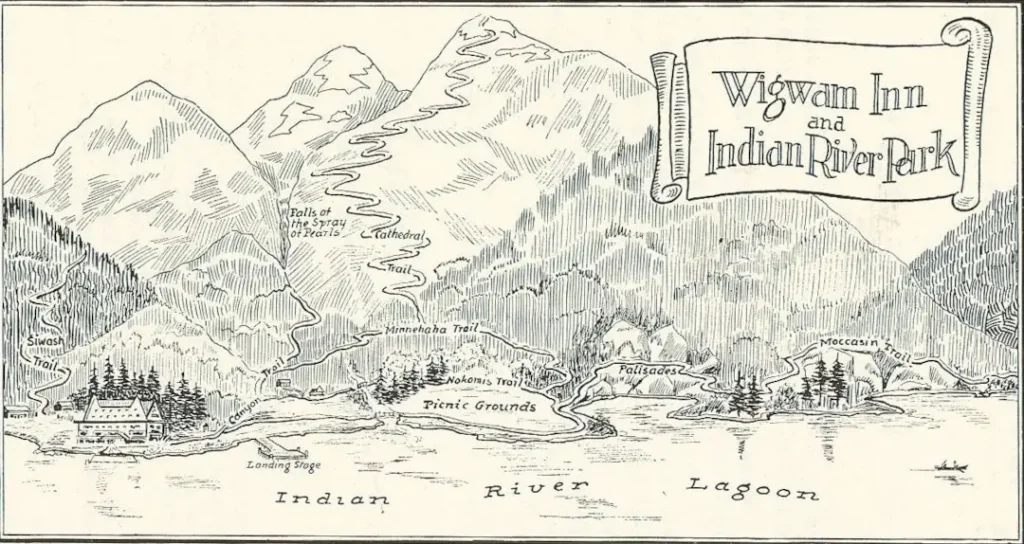

The Indian River Trail was originally a route used by First Nations to reach the Pemberton Meadows area. After the Wigwam Inn was built at the head of Indian Arm in 1910, the overgrown trail was brushed out. By 1916, a route existed from Squamish to several mining camps, and a section of road had been constructed from the other end, with approximately six miles of trail needed to connect the two and reach the rich copper claims in the area. This six-foot-wide wagon path was constructed in 1916.

Today, it’s unknown if parts of the Indian River Trail still exist. A forest service road now connects Squamish to the head of Indian Arm, and a powerline also runs through the area. No maps of the trail itself could be found, but the road likely follows the old trail route based on the location of Windy Creek.

Windy Creek, where the last trace of Warburton was found, appears to be the unofficial name of a small tributary. After much searching, one mention of it was found in a mining report as bisecting a mining claim, and an approximate location was identified through old claim maps. Since the Indian River Forest Service Road crosses the same creek, it likely does follow the old trail route.

Regardless of whether any of it survived, the trail travelled through remote, mountainous terrain and was notorious for being overgrown with salmonberry bushes and devil’s club. Warburton had a pattern of losing obscured trails, and Carre, too, repeated her mistake.

Lost and Found

When Carre didn’t turn up at the end of his holiday time, Constable Gill and a companion set out from Squamish to look for him. Though Carre’s brother offered to charter a plane to search, Gill, knowing the area very well by this time, declined the offer, because it was easier to search on foot. The two men set out on the 56-kilometre trail at 3 am on Saturday, August 22.

No sooner had they set out than Carre turned up. On Saturday evening, he walked into Squamish, where his worried wife waited for him. Exhausted and weak, he was admitted to the hospital and then sent home to recover, none the worse for wear.

Fifteen hours after they’d set out, Gill and his team returned, coming into town on Sunday morning, having travelled the entire distance to Indian Arm and back. During their search, they’d found traces of Carre, indicating that he’d started back towards Squamish on a different trail. They’d tracked him all the way back, but he beat them there.

Carre had only intended to be on the trail for a week, but mistook Indian River for Dow Creek and went in the wrong direction. Why his wife hadn’t raised the alarm sooner can probably be chalked up to thinking he had just taken extra time, with no need to worry until he didn’t show up for work.

Carre was lost on the trail for eight days, eating berries to survive after running out of food. Without a historic map of the region, it’s impossible to trace either his route or Mary Warburton’s. It’s easy to imagine him pushing through overgrown branches, or stepping from rock to rock alongside a rushing creek, his eyes hoping to spot a bit of ragged fabric or weathered bone.

What began as an obsession with solving the Warburton disappearance ultimately led him down the same path, into the wilderness where she had gotten lost. Had he not chosen to go in August, he likely would have suffered the same unknown fate. In the end, that rugged land released him, but not before he truly learned what it was like to vanish.