Five Weeks Lost: The Mary Warburton Story, Part II

In 1926, 57-year-old Mary Warburton was rescued after five weeks lost in the wilderness between Hope and Princeton. Her story was sensational, prompting interviews in which she told her tale. Undaunted by her ordeal, Mary headed straight back to the mountains she loved so well, year after year, until once again she ran into trouble. The second time she vanished in the wilderness, she was never found.

Wandering the Wilderness: Mary’s Story

“I made up my mind I could never be lost if I kept going. I made my imagination serve me, and I tried to keep my mind occupied by striving towards some new objective.”

– Mary Warburton

The weather was so fine on August 25 that Mary Warburton discarded her groundsheet and a few of her extra clothes before leaving Hope. Clad in the hiking clothes of her era, she set out on that warm, sunny day at a brisk pace, making it around thirty kilometres before bedding down for the night. In those days, that meant finding a nice tree for shelter and sleeping under a blanket on the ground.

Drizzle welcomed her the next morning, soaking her gear as she confidently followed the trail into the mountains. With everything around her drenched, there was no fire that sleepless night on a plateau. Not that Mary was bothered much by her situation, as she would later tell reporters: “I was wet and shivering, utterly miserable, but not a bit disturbed by my circumstances. I was sure I was on the right trail.”

Waking cold and wet, her appetite was so low that she threw away her breakfast and used her bacon to start a fire. Then she was on her way again.

Thinking she was at the summit and Princeton was just ahead, Mary was puzzled when the trail petered out on the edge of a slope overlooking a river. Unworried, she figured she was looking down at the Whipsaw River, which would take her to Princeton if she followed it. Follow it she did, while unbeknownst to her, she was following what was probably the Tulameen River deeper into the wilderness.

For three or four days, she followed the river, occasionally spotting a blaze on a tree that would lead her across it. During this time, she slipped on a log while crossing a creek, spilling most of her food into the water. A handful of raisins and what was left of half a pound of butter were all Mary had to eat for the next twenty-six days. Sometimes she’d chew on leaves or fungus, but other than that, she’d have a tiny bit of butter in the morning and evening. Water was plentiful.

Many of her matches were used up one night when a bear came sniffing around her camp. Lighting match after match to scare it off, she was eventually successful, and it wandered away. Another time, she saw a wolf, but it hardly paid her any mind.

Eventually, the river flowed into a gorge. It was so steep that when she tried to climb down the side, she got stuck there, unable to go up or down. Eventually, she climbed back up, hauling herself using bushes. At the top, she spent the night in the rain. The fire she lit for warmth spread into the moss, and she had to rip it up with her bare hands to stop it spreading.

Finding another trail, she followed it for two days, only to be dismayed when it led her back to the same gorge. It was at this time that she decided to backtrack west to Hope. Once again following the river, she crossed it back and forth, sure that the trail was there somewhere, but never finding it. Sometimes she’d climb up to get a view of the land, but more often than not would find it shrouded in mist.

Time and time again, she’d find blaze marks on the trees, leading her astray and then disappearing. Later on, she learned that they were made by topographical surveyors, but at the time, they seemed like poorly made and unfinished trails. Her lowest moment was following one up a steep hill for hours, only for it to end in nothing.

“I never gave up. To the very last hour I kept trying something new. I tried going north and sometimes south.”

By the third week, her body was growing weaker. Her arms and legs were cut up from the undergrowth, her clothing in tatters. Nights were spent with her feet in her knapsack, with a dry pair of socks and some moccasins for warmth. All night, she’d pinch her legs to keep the circulation going.

A blizzard came that week. Making a shelter of branches, Mary huddled there for three days and nights. They were long, sleepless nights. She’d pass the hours in the darkness by singing or humming all the songs she knew. She’d think about stories she’d read of others who’d been lost like her. She would dream about people putting her on the right trail, only to awaken alone in the forest. Sometimes she played cards and dabbled with telling her fortune with them.

When the storm abated, she trudged through melting snow. Another trail led her to a crumbling prospector’s cabin, just in time to protect her from another blizzard. For two nights, she sheltered there as the snow fell, with frozen water and no matches. Then she discovered a tin in the cabin, and was overjoyed to find that it contained matches. Once again able to have a fire, she lit one in a corner of the cabin, only to have it spread to the floor and catch the whole place on fire.

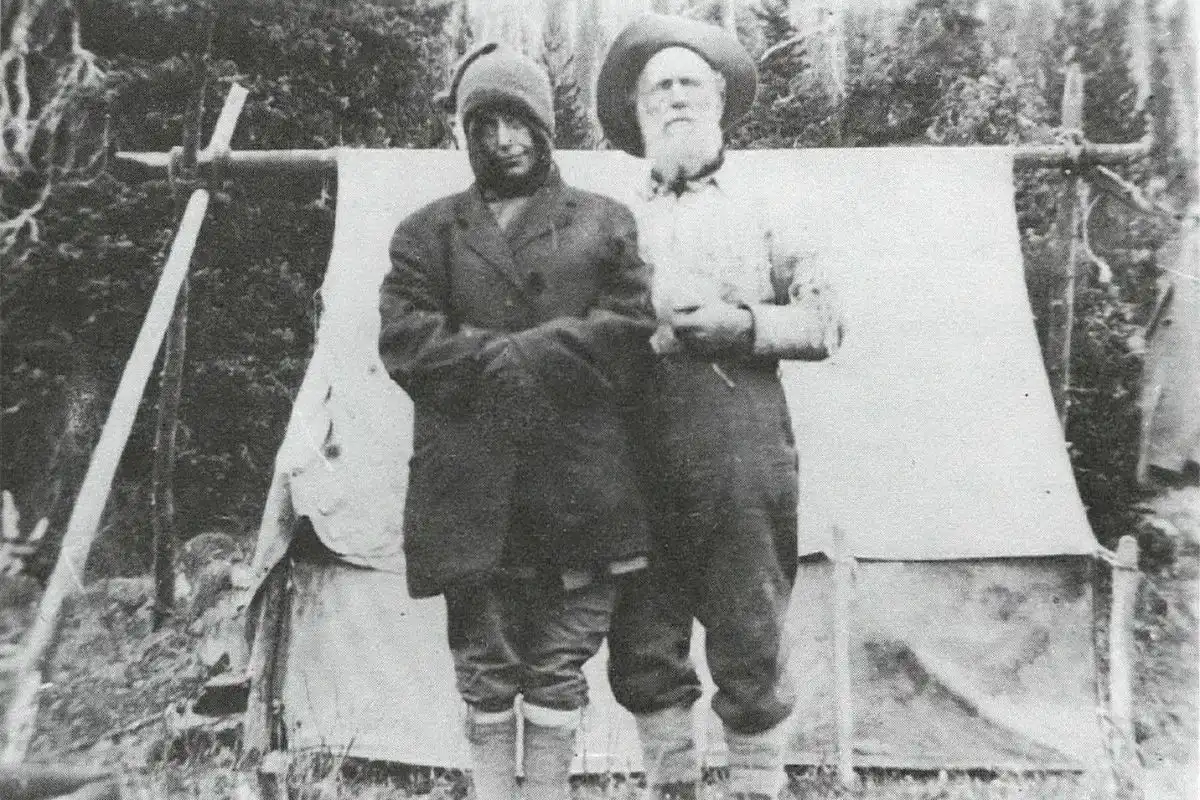

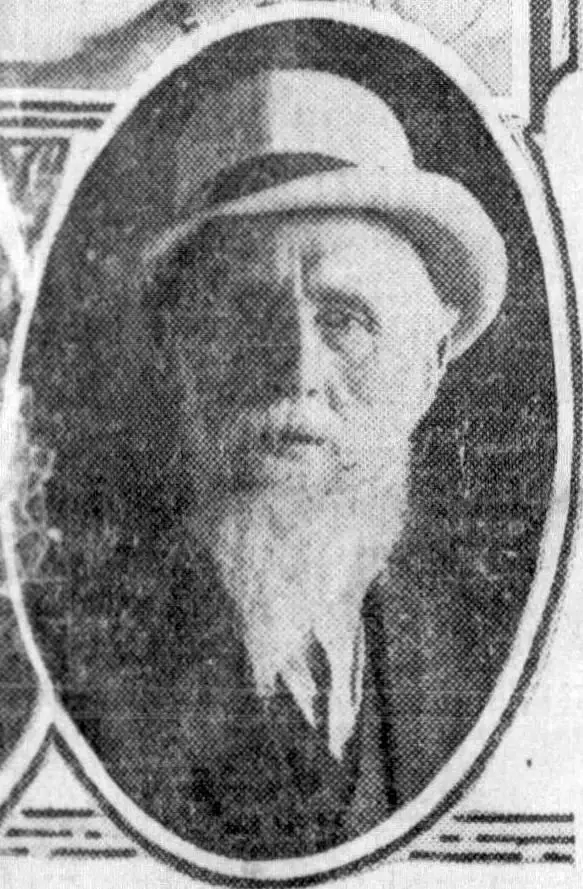

Unbeknownst to her, those matches had been left in the cabin by none other than Podunk Davis himself, who would soon become her rescuer. At the time, he’d remarked to a companion that the matches might just prove useful to someone, someday, and two weeks previous, while searching for Mary, he’d replenished the supply.

With her shelter gone, Mary waded through snow, climbing upward and westward. With her strength waning, she stayed two days on a hill at the edge of a valley, warming herself when the sun returned. Unable to walk and very thirsty, she figured she was going to die, so she started sharpening her knife on a stone. As a nurse, she knew that bleeding out made people thirsty, and she wanted to die in comfort. She planned to go down to the river and drink her fill while she cut her radial artery and bled out.

On the way there, however, she came across a small creek that slaked her thirst, reviving her enough that she decided to keep going. Deciding to go back to the cabin she’d burned down, she started making her way there. After two days, she spotted smoke from a campfire. Calling out a couple of times, she found her cries answered by rifle shots, and joyfully made her way towards the sound.

The man, with his snow white hair and beard, looked just like an angel, and she told him as much as she threw her arms around him. It was none other than Podunk Davis, whose thoughtful matches she’d found, and who was now her rescuer. Later on, she’d joke about it: “And then a dreadful thing happened. I threw my arms around the neck of a man I had never met before.”

It almost seems like fate was at work, ensuring Mary’s survival. The very matches she’d found, that had likely saved her life, had been left (and replenished) by Podunk Davis. His intuition later led him straight to her.

Mary Warburton, or Nurse Warburton as she was often called in the papers, gained brief fame for her ordeal. Newspapers interviewed her, publishing stories about her five-week survival in the BC wilderness. Wood’s Shoes, where she’d purchased hers the year before, proudly displayed her tattered oxfords in their window.

“My greatest fear, at the end, was that I might become crazed,” Mary told reporters. “Podunk, who has found six men in that country, says every one has been crazed from the exposure even though they have been out but two or three days.”

Podunk Davis was hailed a hero. Mary’s brother sent him a silver match case from England, engraved with the words he’d uttered when he’d left the matches in that old cabin: “May prove useful to someone, sometime.” The following spring, he and Mary met again when he was awarded a bronze lifesaving medal by the Royal Humane Society. Premier Oliver attended the ceremony in Princeton.

It didn’t take much for Mary to bounce back from her ordeal. Just a week later, she walked into the newspaper office to thank the staff, who were astounded at her cheery disposition and blasé attitude about the whole thing: “To me it seems like people have overestimated my troubles. Looking back, I am only conscious of the fact that I never lost hope.”

After her recovery, Mary went back to work at a Vancouver hospital, taking up nursing again. Though she’d mentioned that she’d like to go back and successfully complete the trail the next year, nobody took her seriously. So she kept her plans a secret.

Going Back: 1927-1931

“There is something irresistible about the Hope mountains.”

– Mary Warburton

At the junction that was so poorly marked, signs had now been posted, and blazes cut into the trees. When Mary Warburton came upon them in August of 1927, a year after getting lost in the wilderness, they led her down the correct trail this time. She hadn’t told anyone that she was going to try and do it again, so when she walked into Princeton four days later, it was to the astonishment of the townsfolk.

Considered strange for her habit of long walks around the province, Mary was fiercely independent and not the least bit put off by the previous year’s adventure. A friend joined her by train in Princeton, and the two of them headed to Penticton to pick fruit. They hiked to Hedley, then took the Old Nickel Plate Road to their destination. In the autumn, Mary returned to Vancouver by hiking the train tracks from Brookmere to Hope.

The next year, she was at it again. She took the train to Jessica Station and hiked to Princeton via Dewdney Creek and the Dornberg Trail. At one point, she nearly got lost again when the trail grew overgrown and fog rolled in. Not one to lose her head, she simply made camp, then climbed a nearby hill the next morning and spotted a road.

In 1930, she took the southern Skyline Trail to Princeton for her yearly fruit-picking tradition. She ran into heavy snow that obscured the trail, but managed to follow some marten tracks and once again narrowly avoided getting lost.

The following year, she followed the same route, coming out at Copper Creek and catching a ride on a government truck into town. There, she visited with friends, telling them her plans for her return to Vancouver. First she was going to head for the Cariboo and Barkerville, then come back down through Lillooet to Squamish, following the rail line.

Clad in her hiking garb with a 30 lb pack containing her usual supplies, a silk tent, and food for two weeks, Mary Warburton confidently set out on her trip. Little did she know that it would be her final one.