Is this the Most Dangerous Place to Hike in BC?

With so much variation in terrain, the most dangerous place to hike in BC is up for debate. There’s no question that Vancouver’s North Shore Mountains are a hotbed for search and rescue activity. Anywhere there are more people venturing into the backcountry, there will, in turn, be more misadventure. This is also why you see provincial and national parks as hot spots for injuries, accidents, and getting lost.

Some outdoor activities come with inherent risk, such as climbing and mountaineering. Others, such as mushroom foraging and hunting, can be riskier because they take people off-trail. Any trail-based activity, like hiking, is fairly simple: stay on the trail, and you won’t get lost.

The question of which wilderness area in BC is the most dangerous depends on the criteria. Weighing by activity, terrain, and population will produce different results. The worst-case scenario for hikers is death. The worst-case scenario for their loved ones is never being found.

Hiking deep into the vast wilderness of the Coast Mountains is near impossible. Glaciers, mountains, overgrown routes, wildlife, and thick temperate rainforest make any off-trail travel a daunting trek. Only a handful of people have ever traversed the entire range. Wisely, most people stick to accessible areas. To the south of the Coast Mountains, an entirely different mountain range is particularly accessible…and dangerous.

The North Cascades

Divided by the Fraser River, the Cascade Range lies south of BC’s Coast Mountains, with the majority in Washington State. Making up the northern part of this range is the North Cascades, which includes Mount Baker and North Cascades National Park. The very top end of this range lies within BC, spanning from Chilliwack to Keremeos, and jutting north to Lytton.

Though rugged and challenging, in BC the range is quite accessible in comparison to the vastness of the Coast Mountains. Early on in the history of the province, trails were pushed through, connecting Hope to the Similkameen and beyond. Many historic trails in BC, such as Manning Park’s Skyline Trail, followed pre-existing First Nations routes.

- HBC Trail, 1849

- Whatcom Trail, 1858

- Boundary Commission Trail, 1859

- Dewdney Trail, 1860

- E.C. Manning Provincial Park, 1941

- Hope-Princeton Highway, 1949

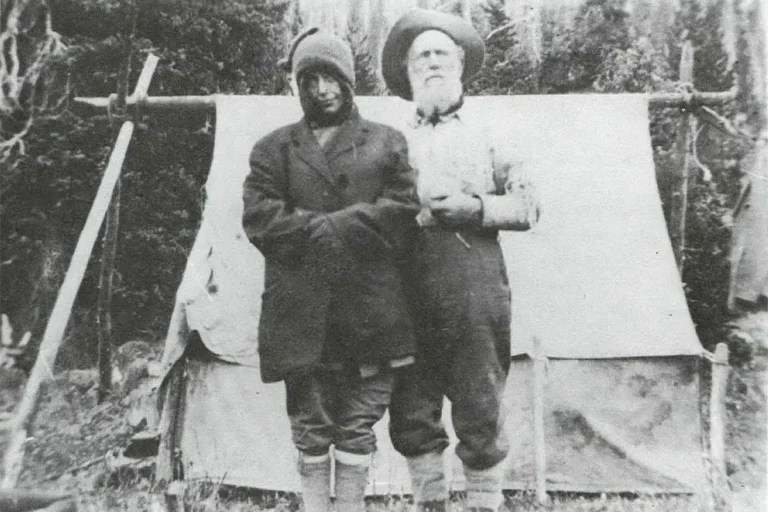

Long before the development of Manning Park and the highway, access to the area could only be done by horse. Though remote, the BC’s North Cascades were well-known to prospectors, settlers, hunters, and ranchers, whose cattle once grazed in the Three Brothers area.

Make no mistake: this is hard, wild country, deceptively inviting. As people began to venture into the backcountry of the North Cascades, they also began to disappear…with a startling number of them having never been found.

The Missing

While researching historic cases of people who have vanished in BC’s wilderness and never been found, I became particularly interested in John Ewing and Mary Warburton. Both went missing in the wilderness between Hope and Princeton, the dead centre of BC’s North Cascades. In turn, while researching them, I found multiple other cases of people having gone missing in the area. Unlike other areas, there was a distinct pattern to the disappearances. A good number of them have never been found.

The list below shouldn’t be considered comprehensive. It’s difficult to track down information on historic cases of people missing in the wilderness. Old newspapers can be tricky to search keyword-wise, and sometimes cases are mentioned and never followed up on. A missing archival death record can also mean someone simply moved out of the province.

- Mary Warburton, August 1926: lost five weeks; found alive.

- John Henry Jackson, October 1929: hunter, found deceased.

- Arthur Olsen, October 17, 1933: hunter, never found.

- John Ewing, October 8, 1955: hiker, never found.

- Harvey Garrison, October 19, 1956: hunter, never found.

- Three men and a child, July 1963: lost five days, found alive.

- Two men, October 1963: hunters, lost two days, found alive.

- Three men, October 1967: hunters, found alive.

- Woman, January 1995: skier, missing one night, found alive.

- Jordan Naterer, October 10, 2020: hiker, found deceased.

In addition to the missing between Hope and Princeton, there are also several outdoorspeople missing in the western end of the range, as it lies in BC. The difference between those cases and the Hope-Princeton cases is that there seems to be a pattern to the latter. Out of the ten known cases, seven of them went missing in October.

The First Snow in the North Cascades

The seven Hope-Princeton wilderness missing cases include all of those who were either found deceased or never found at all. Of the ten cases, many of them involved the first winter snow. Some were lost prior to the now falling, while others were lost partially because of the snow.

Unexpected snow can obscure trails, hide landmarks, and make walking all the more difficult. Off-trail, thick brush and blowdown can severely hamper movement and progress. Manning Park is particularly bad for this today, having been affected by the mountain pine beetle, which has caused significant blowdown, especially off-trail.

Many of the cases were well-prepared or experienced outdoorspeople. They were out on what seemed like a reasonable trip for the season. Unfortunately, October in the North Cascades sits in a dangerous in-between. Summer conditions persisting into the autumn can draw people out for one last trip of the season, unknowingly putting them at risk of being caught in the first winter snow.

A Closer Look

When looking at cases of people missing or perishing in the wilderness, it’s better to learn rather than assign blame. Humans are not infallible. We make mistakes. Examining what happened helps others with their own awareness of risk.

In all but the case of the skier, the individuals got lost. One of Mary Warburton’s rescuers stated in a news story that she was one of seven lost people he’d located over the years. Nothing on those earlier cases could be found.

All of the October cases involved snow, sometimes significantly contributing to their demise. Out on a day hike, one news source indicated that John Ewing intended to cross 30 kilometres of wilderness. While there are some people who do day hikes of this length, it’s far more likely that he was overconfident and misjudged the distance. At any rate, he was poorly equipped for that length of hike at that time of year.

Snow also may have led to Harvey Garrison’s demise. It also helped searchers to track him for several days afterwards. Trudging through the stuff for days can cause fatigue and hypothermia.

In the most recent case, Jordan Naterer was well-equipped, moderately experienced, and had researched the area and hike well. While his movements earlier in the day are unclear, he did register to camp at Frosty Creek. Camping is only allowed in designated sites within Manning Park to protect sensitive habitat. His gear, which for unknown reasons he was separated from, was not found at the campsite, but rather up on the larch plateau. This doesn’t mean that he didn’t intend to go back down to the campsite, only that he got lost at a higher elevation, with the snow ultimately being the cause of this.

Lessons From the North Cascades

It’s difficult to definitively name the most dangerous place to hike in BC. Danger shifts depending on terrain, weather, and population. But if patterns matter, the North Cascades stand out.

Manning Park itself is not inherently dangerous. In fact, popular routes like the Mt. Frosty larches are among the safest hikes in the province during peak season. The trail is well-worn and highly trafficked.

Again and again, the same conditions appear: experienced outdoorspeople, reasonable objectives, late-season trips, and the first winter snow. For the most part, none of the missing were reckless or had unreasonable objectives. It’s a specific set of circumstances that turns trips deadly.

It’s going off-trail where problems can happen, whether accidentally while hiking or purposefully while hunting in wilderness areas. Unfortunately, in adverse conditions, falling snow can erase the trail itself, and low visibility can make wayfinding by landmarks impossible.

When these four factors align, the consequences can become severe:

- Location: North Cascades

- Time: October

- Situation: Lost off-trail

- Weather: Snow

This is where reasonable trips turn fatal, and people can vanish without ever being found.

The lesson of the North Cascades is not fear, but respect. October here is a threshold. Cross it unprepared, and the mountains stop forgiving mistakes.

And the first winter snow comes suddenly and silently when it falls.