Missing in the BC Backcountry: The Forgotten Story of John Ewing

Even decades ago, the story of a missing hiker starts the same: someone goes out and doesn’t return. A search begins. In most cases, the person is found. But some missing hikers are never found. They vanish as if into thin air, their fate hidden amongst jagged rocks, deep gullies, and raging creeks. The disappearance of British lawyer and mountaineer John Ewing in 1955 is one such case. Today, his story stands as an early example of what would now be classified as a cold case in the BC wilderness.

Born in England in 1915, Ewing was the son of Sir James Alfred Ewing, a renowned physicist and engineer, and Lady Ellen Lina Hopkinson. Both the Ewing and Hopkinson families were experienced in mountaineering, and tragically Ewing was not the first in his family to suffer a mishap. In the summer of 1898, his maternal grandfather, John Hopkinson, along with a son and two daughters, perished in a mountaineering accident in the Swiss Alps.

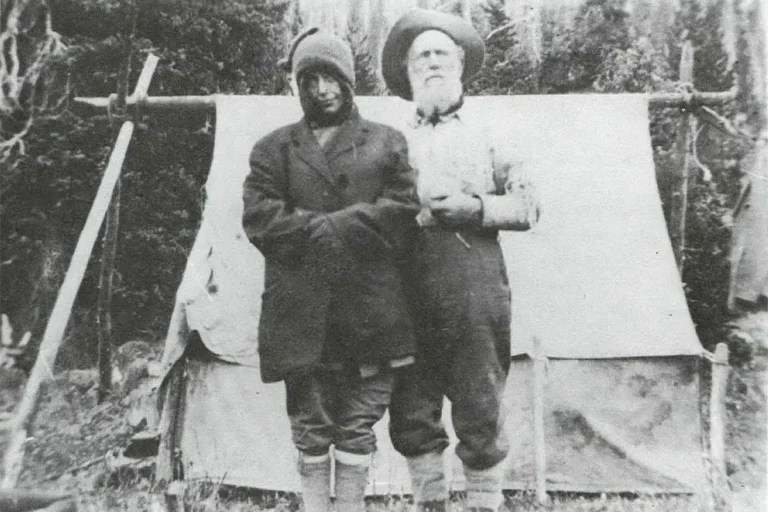

Ewing had a privileged upbringing, with his family’s wealth allowing him to travel and study law, ultimately becoming a lawyer. He married Diana Fryth, a doctor of psychology and writer who had studied at the Sorbonne in France. Both were experienced in the outdoors and had climbed in the Alps many times. During WWII, Ewing was a Lieutenant in the Royal Air Force, and was stationed in Victoria. After the war, the Ewings lived in Toronto but frequently visited friends in Vancouver. In 1952, they permanently relocated to British Columbia, ultimately settling in Princeton, BC.

On Saturday October 8, 1955, forty-year-old John Ewing set out to explore the Hope-Princeton Trail (Old Dewdney Trail) near Whipsaw Creek. His plans were to follow the trail for awhile, then cut across several kilometres of wilderness to the Hope-Princeton Highway and find a lift home. He was lightly clothed, wearing oxford shoes and carrying two bars of chocolate. While he had mountaineering experience in the Alps, he was unfamiliar with the rugged terrain of the British Columbian wilderness.

The evening, the first snow of the season fell. Ewing did not return home. A search was launched, but the snow, waist deep in some places, obscured any tracks that may have been left. Determined to find her husband, Mrs. Ewing chartered a helicopter to help the search, which supplemented two planes, thirty volunteers, two tracking dogs, six RCAF ground searchers, RCMP Officers, and fifty soldiers from CFB Chilliwack.

Authorities believed that Ewing ran into trouble when trying to traverse from the trail to the highway in the snow. The search area in the Whipsaw Basin amounted to 72 square kilometres, with elevations reaching over 1500 metres. The area was rugged, with heavy undergrowth that combined with the snow made it completely impassable in some areas.

Footprints were seen in the snow south of Whipsaw Creek, which gave new hope to searchers, whose numbers had grown to 125 and included Mrs. Ewing herself. By five days in, the snow had all melted, but no sign of Ewing was found. On October 16, eight days after he went missing, the search was officially called off.

Shortly afterward, two hunters came forward and reported having seen Ewing on the day he went missing. They had spoken to him and said that he had warmed himself by their fire. With this new information, a small party of five officials went in on horseback to search west of where the hunters had seen him.

No trace of Ewing was ever found.

In December, Ewing was declared dead by court order. A little over a year after his disappearance, in an eerily similar case, eighteen-year-old hunter named Harvey Garrison disappeared in the same area. Separated from a hunting companion, he got lost in the wilderness and despite a nine day search, ultimately suffered the same fate as Ewing.

Before modern GPS and satellite phones, hikers faced the BC wilderness with far fewer tools, and yet the reasons hikers go missing remain much the same as today. As recently as 2020, hiker Jordan Naterer got lost in a snowstorm and perished in Manning Provincial Park, not far from where Ewing and Garrison suffered a similar fate. While Naterer’s remains were eventually found, his case underscores a sobering reality: whether in 1955 or today, the risks of underestimating BC’s wilderness have not changed. Historic missing hiker cases like Ewing’s serve as reminders of the enduring power of the wilderness.

If you’re interested in another BC missing hiker cold case, check out the story of how Evans Peak got its name.