The First Disappearance: The Mary Warburton Story, Part I

“Lines, from Tennyson, I think, kept recurring to me while I was lost. A land where no man is or has been since the making of the world.”

– Mary Warburton

In 1926, when 56-year-old Mary Warburton was rescued after five weeks in the wilderness between Hope and Princeton, the story made the news as far away as England. Five years after her ordeal, she was caught up in another one. In an attempt to hike from Squamish to Indian Arm, she once again got lost. Despite an extensive search, she vanished in the backcountry and was never found.

Mary’s love of the mountains took her straight back to them year after year. Though they eventually took her life, her story of survival in the British Columbia wilderness is incredible. Strangely, it remains largely unknown today, forgotten in old newspapers and periodicals.

It deserves to be told.

The Early Years

“My sister has always loved walking. On holidays in the Old Country she has walked through the wild parts of the west of Ireland.”

– Susan Warburton Lott

Little is known of Mary Warburton’s early years or when her love of long walks in the hinterlands began, but her ancestry can be traced by way of a handful of records. Born Ada Mary Warburton, she came into the world on May 30, 1870, in Manchester, England, to Alfred and Martha Warburton (née Pollitt). Her mother died when she was a child. Her father remarried, and a few years later, passed away as well. As a young woman, she went to Scotland to train as a graduate nurse and worked in the Glasgow Infirmary.

Mary loved walking and the outdoors, and was said to have gone hiking alone in Scotland and Ireland. She was athletic, liked to eat healthy, and was very independent. Rather than marry, she chose to stay single and work as a nurse, mostly in private homes. In the early 1920s, her sister, Susan, had immigrated to Vancouver, British Columbia, and married there. In 1923, Mary made the move herself and joined her.

In BC, she took up nursing in private homes during the winter, and in the summer would take to the great outdoors. She made yearly pilgrimages to the Okanagan to pick fruit, and more often than not, she walked there and back. In 1923, she and a friend wanted to return from their fruit-picking season by way of the Hope-Princeton Trail, but were talked out of it. Instead, they hiked to Coalmont and followed the Otter Valley through to Brookmere, where they caught a train south. After getting off at Ruby Creek, they walked over 140 kilometres from there to Vancouver.

That same year, Mary visited the Dease Lake area. Evidently, she was intrigued by mining and gold rush history, because it was reported that she visited many of the mining regions of the province.

In 1924, on her way to go fruit picking, she took the train to Princeton and walked to Osoyoos. From there, she took the Richter Pass Trail to Keremeos.

While it’s likely that she walked to many more places than were mentioned in secondary sources of information, it’s clear that Warburton wasn’t afraid of long-distance hiking in remote areas. Soon, however, her love of long walks in the wilderness would land her in trouble.

The 1926 Disappearance

“The weather was foul, and I never thought anyone could stay alive, and sane, alone in those mountains.”

– Constable Fred Dougherty

The wilderness was calling, and Mary Warburton wasn’t going to be deterred from walking the Hope-Princeton Trail this time. It wasn’t for lack of trying on the part of the Hope RCMP, though, when she informed them of her plans.

She was travelling light, bringing along a pen knife, frying pan, coffee pot, spoon, light blanket, an army ground sheet, and four days’ worth of food. She’d also purchased a government map of the area, on which the route had been drawn by a friend. She expected to complete the 104-kilometre trek in four days and three nights.

She set out on August 25, passing by a couple of trappers who were just finishing a journey from Princeton to Hope with some tourists. At mile twenty-three of the trail, she knocked on prospector Robinson’s door at Camp Defiance, but it was early, and by the time Robinson had risen from bed and dressed, she was gone. Five days later, he saw her tracks going up the Canyon Trail and was alarmed. The trail, overgrown and having fallen into disuse, petered out a few kilometres up into the mountains.

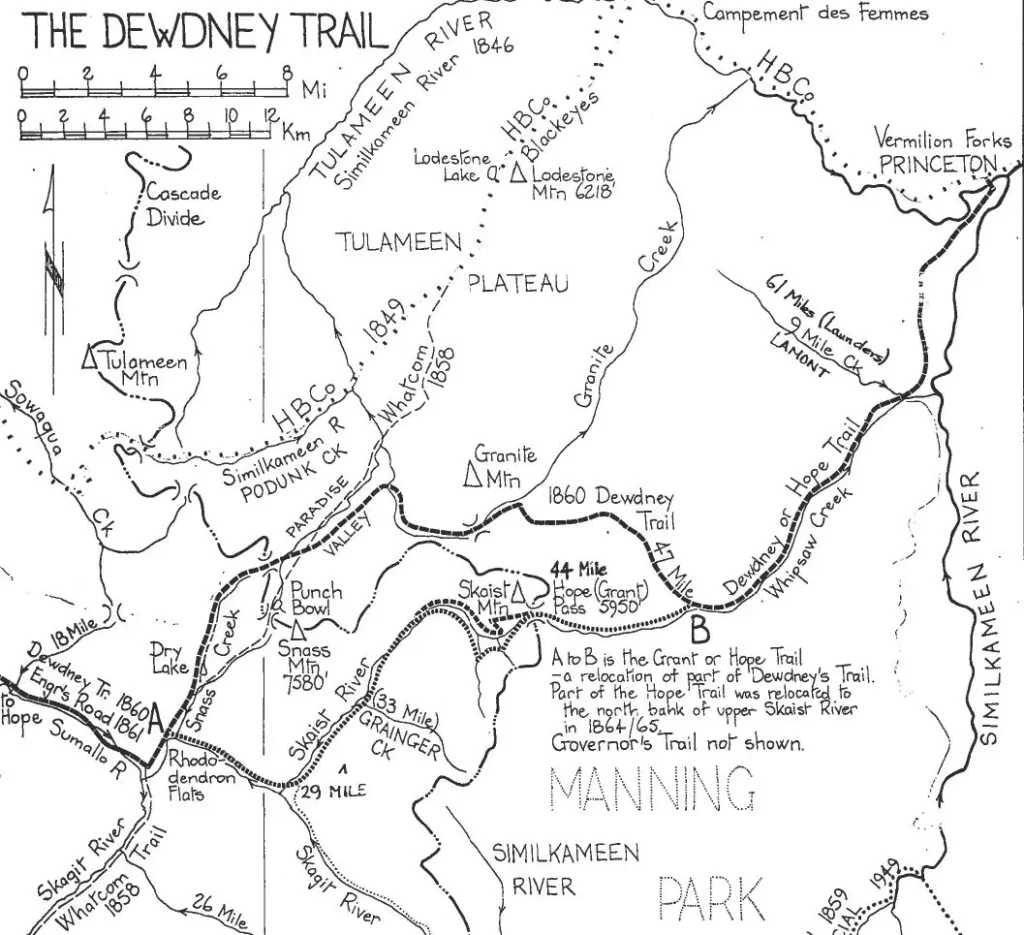

At the time, both the Canyon Trail and the Hope-Princeton Trail were branches of the Dewdney Trail. The Canyon Trail was the original Dewdney route, while a later branch (today known as the Hope Pass Trail) became the main route. In Mary’s time, the Canyon Trail was in poor condition. A century on, a stretch of the old route is constantly swallowed by brush. (In fact, even as this story is being written, a volunteer crew is planning to brush it out yet again.)

The junction between the two trails was deceptive, as the Canyon Trail continued in the same direction as the main trail, while the main trail appeared to go south. It later swung back northeast. Since the junction was poorly marked, Mary continued on what appeared to be the main trail.

After tracking Warburton up the Canyon trail for 11 kilometres, Robinson sent word to Hope that she was on the wrong trail and a search party should be sent out. Meanwhile, the trappers she’d passed on her first day had returned to Princeton and hadn’t overtaken her on the trail as they’d expected to. They reported to Constable Barrington-Foote in Princeton that she was overdue, and after conferring with the Hope RCMP, a search was mounted.

Search parties were sent out from Hope, Tulameen, and Princeton, but aside from a fire pit and some tracks, no sign of Mary’s path was found. For weeks, they searched the backcountry, and then the first snow of the season fell. Winter was setting in, and Mary would have run out of matches. Near the end of the month, the search parties returned to Princeton. Hope of finding her alive was beginning to wane.

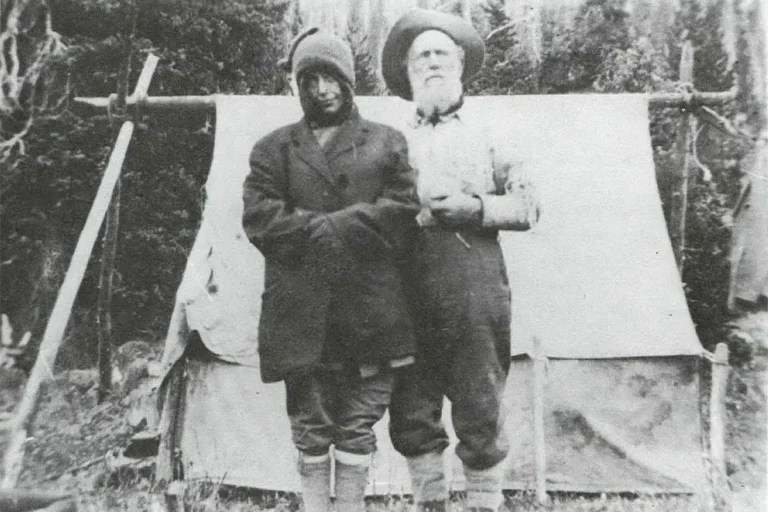

With October just a few days away and the weather poor, the search had quietly changed course: they were looking for a corpse. Even Mary’s sister believed she was dead, and her brother-in-law offered a $100 reward for anyone who found her body. In one last bid to find it before it was buried by winter snows, Barrington-Foote sent out a final search party, made up of Constable Dougherty and a local prospector named Willard “Podunk” Davis.

Davis knew the country like the back of his hand. They rode up the Canyon Trail to Paradise Valley, where Warburton’s tracks had been seen. When looking for an area to set up camp, something told Davis to go left instead of right, as they’d originally intended. They had started a fire and were setting up their campsite when a voice nearby called out, “Hello!”

After firing several shots into the air, Podunk Davis plunged into the undergrowth, where he found Mary Warburton, weak and leaning on a walking stick as she tottered towards him. She’d seen the campfire smoke. Throwing her arms around his neck, she told him he was an angel from heaven.

Her clothing was in tatters, the soles of her shoes tied to her feet with strings. Weak, emaciated, but lucid, Mary was very much alive and in possession of all her faculties. The men carried her to camp, where they fed her broth and warmed her by the fire. The next day, they put her on one of their horses and rode to a cattle camp, where word was sent out to Princeton that she’d been found alive.

Constable Barrington-Foote and his wife, upon receiving word of Mary’s miraculous survival, immediately set out with clothes in their horse and cart. After arriving back in Princeton, she was taken to the hospital. She weighed 80 pounds. Mary, despite her body’s poor condition, wasn’t about to get right into bed. She wanted a bath first, which she did, unassisted. Meanwhile, her incredible survival story was making the news across North America. Five weeks alone in the British Columbia wilderness was nothing short of miraculous. Very soon, she would tell her tale of survival. It was wilder than anyone could have imagined, driven by her determination and a strange twist of fate.