The Last Trail: The Mary Warburton Story, Part III

Undaunted by being lost in the BC wilderness for five weeks, Mary Warburton kept going back to the mountains. In 1931, while hiking from Squamish to Indian Arm, she went missing for a second time. Despite an extensive search, she was never seen again, and her legendary survival story has been largely forgotten.

The 1931 Disappearance

“She was quite annoyed when I complimented her for being so brave.”

– Kathleen Barrington-Foote

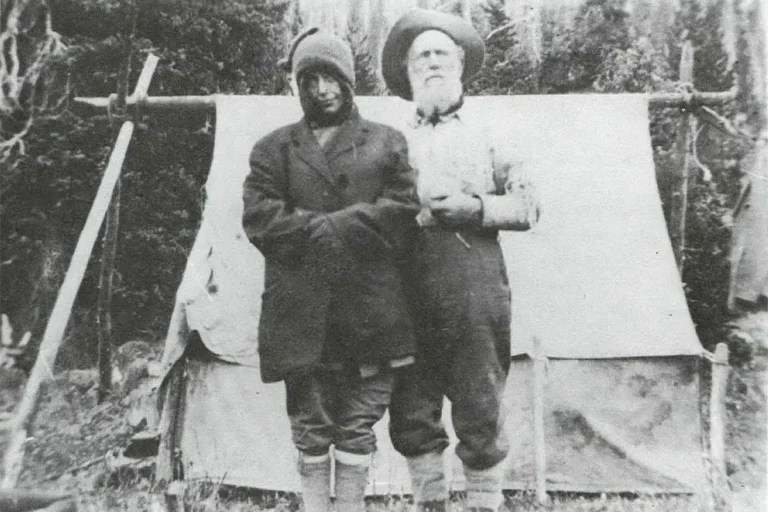

A postcard sent from Cheekye Station, 16 kilometres from Squamish on the PGE Railway, was the last time Mary Warburton’s family heard from her. In Squamish, she left her trip plan with Constable Gill of the RCMP. She intended to follow the Indian River Trail from Squamish to Indian Arm. Once again, she was travelling light, with no more than ten days of food.

She departed on October 19, but by the beginning of November, she was overdue. Once again, a search was mounted for Mary Warburton. Though her friends speculated that she could have changed her plans and gone elsewhere, she should not have been gone more than a week. Though she was overdue, she’d survived weeks in the wilderness before.

Searchers set out along her intended path along the Indian River, and quickly found evidence of her having been there. A note written on paper torn from her diary, dated October 22, was found in an old cabin just a day’s walk from Squamish. It stated that she was okay, had been held up by snow, and had used some firewood.

A day’s walk further on, searchers found a spot where she’d pitched her tent, and another half day’s walk from there, found a woman’s footprints in the snow. The trail then went cold, with newly falling snow obliterating her tracks.

Search parties took a week to cover the Indian River Trail, with no other sign of her found. The conditions were treacherous. The trail was rough and overgrown, and snow had covered the trail entirely in some areas. The creeks were swollen with rushing water. Still other parties searched the trail between Seymour Creek and Britannia Mine in case she’d gone that way. They found the snow a foot deep at the top of the divide. Since the camp and footprints had been found after the Seymour Creek Trail turnoff, the searchers didn’t think she’d gone that way.

There was such difficulty in hiking the trail that searchers donned snowshoes the next time they went out. By this time, winter had arrived in full force, depositing six feet of snow in the search area. They visited several hunters’ cabins, thinking she was holed up in one, but none had been used.

Further searching was hampered by snow, and when the final group of searchers returned on November 21, the search was abandoned. They had covered all possible trails with no further sign of her and believed her to be dead.

Mary Warburton had gone on her final hike. The mountains had taken her, leaving her fate a mystery.

Never Found

“She was one of those peculiar individuals who spent her holidays walking around the hills.”

– Mr. F.R. Anderson

Mary Warburton’s pattern of losing her way on overgrown or obscured trails was likely what led to her demise. After her first ordeal, she stated, “And all through it, I feel that I never lost my way. I was always heading for some place.” Though it’s difficult to know what she was thinking, her losing the trail on at least two other occasions points to her learning little from her experience.

Her body may never have been found, but in the mountains she loved so well, Warburton Peak stands as her monument. Located in the backcountry between Hope and Princeton, the nearby Warburton Camp and Warburton Loop Trail were also named for her.

At the request of her sister, Mary Warburton was declared legally dead in 1934.

In 1936, a piece of human skull was found in the bush between Squamish and Vancouver. There was some discrepancy as to the exact location it was found, with one news report saying it was “near the height of land between South Valley and Loch Lomond, at the headwaters of Seymour Creek.” Another reported the location as “Petgill Lake, two miles from the Britannia Mine.”

Regardless of where the bone was picked up, nobody seemed to think it belonged to Mary Warburton, as the last evidence of her was found far beyond the area. Still, given that she’d survived five weeks in the wilderness before, one has to wonder if Nurse Warburton’s resilience could have once again taken her far beyond anyone’s expectations.

Ahead of Her Time

I stumbled across Mary Warburton’s story by chance, while researching British Columbia’s historic missing hiker cases. It came up in passing in an article long after her death, and I was surprised that it hadn’t shown up in my previous searches. The more I read about her story, the more she seemed like a woman ahead of her time.

If you dropped Mary Warburton into today’s world, she’d be considered an ultralight backpacker and thru-hiker. Though she was criticized for being unprepared, that same criticism follows ultralight hikers today. Mary also did something that today’s hikers are encouraged to do: she left a tip plan. It was this trip plan that sparked the search for her during her first time getting lost.

Even today, surviving alone for weeks in the wilderness is considered miraculous. Wilderness survival stories are somewhat revered, sparking intrigue and fascination, circling around the core question: can the human animal, so long removed from nature, still survive in it? Those missing hikers who are lost and never found leave the rest of us wondering what happened. The end of the story leaves a nagging mystery.

The British Columbia backcountry is rugged and unforgiving. The wilderness between Hope and Princeton has an eerie feeling to it. Nothing ever went well when I camped alone in Manning Park. Even before a thunderstorm at Mowich Camp had me terrified out of my wits, the place felt spooky. Then there was an overnighter at Kicking Horse Camp on the Heather Trail, where an inadequate sleeping bag had me stuffing my legs into my backpack for warmth, just like Mary had done when she was lost.

There’s something haunting about a land that keeps swallowing people. Mary Warburton was lucky. Others taken by the same land were never spat back out alive, or at all. In the same wilderness where she was lost the first time, John Ewing disappeared and was never found. He’s one of three such cases in the area. The backcountry where Mary vanished for good has also claimed a number of people, some of whom, like her, remain missing. When I think of them, I’m reminded that the first autumn snows can so easily go from wonderland to funeral shroud. The wilderness we love so well is indifferent to our wayward steps.

All night in a waste land, where no one comes,

Or hath come, since the making of the world.

– The Passing of Arthur, Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Read on: The Lost Searcher: Edward Carre and the Warburton Mystery